If there’s one thing photographer Dan Bolt likes, it’s a new toy – in this case a torch with a ‘blue light’ setting that he has been using to show Britain’s fluorescent fauna in a new light.

If you’ve read any of my previous articles, you’ll know I’m an avid UK underwater photographer with a special love for our endlessly varied marine life. I’m also keen to use new techniques or kit to help me shed new light on some of the more unusual things that go on beneath the waves.

In that vein, earlier this year I purchased a bit of kit called a ring-light: quite literally a circle-shaped torch. Often used in fashion photography, ring-lights give photos a very distinct look and feel, but quite by accident (who reads a manual?) I found out that the one I had purchased also has a blue-light mode that was designed to show off something called ‘fluorescence’.

For those of you (us!) of a certain age, you may remember the disco scene back in the 80s, when they would use a special blue light to make your eyes, teeth, and any brightly-coloured clothing glow in the dark. Generational tastes aside, the effect was really quite something. Roll on another 30 years and this ‘look’ was used to great effect in James Cameroon’s 2009 film Avatar – where much of the imagined flora and fauna indigenous to a far-off world glowed with an inner, other-worldly light.

In truth, those two examples of something ‘glowing’ are quite separate, despite seeming to show the same behaviour. In the disco we were seeing certain objects that were absorbing the blue light and re-emitting it on another wavelength, ie: a different colour to the blue light that was hitting them, this is fluorescence. In Avatar, the glow came from within the imagined creatures themselves, which is caused by a mixing of two chemicals to produce light; this is known as bio-luminescence (well, it is on earth anyway). You’ll have seen the same thing on a night-dive if you’ve ever seen those flashes of light given off by some plankton species as you swim through the water – or in your glow-stick after you crack and shake it to mix the chemicals.

Your own personal Avatar

So back to the plot, and my blue torch. This is a different kind of blue that was used in those 80s discos (that was mostly ultra-violet) and is designed to energise certain species into fluorescing. My first couple of dives with it were very experimental, and to be honest quite disappointing.

I was expecting everything I shone the blue light at to immediately explode with a kaleidoscope of new colour… oh how wrong I was. As it turns out there are relatively few UK marine species that fluoresce to order, but happily for me, those that do can be found on my regular circuit of dive trips.

In a pleasing twist, it turned out that the first reported sighting of fluorescence in an anemone was made on my home patch of Torbay. In May 1927, Charles E.S. Phillips reported in the journal Nature, that he had observed this behaviour in an anemone in bright daylight.

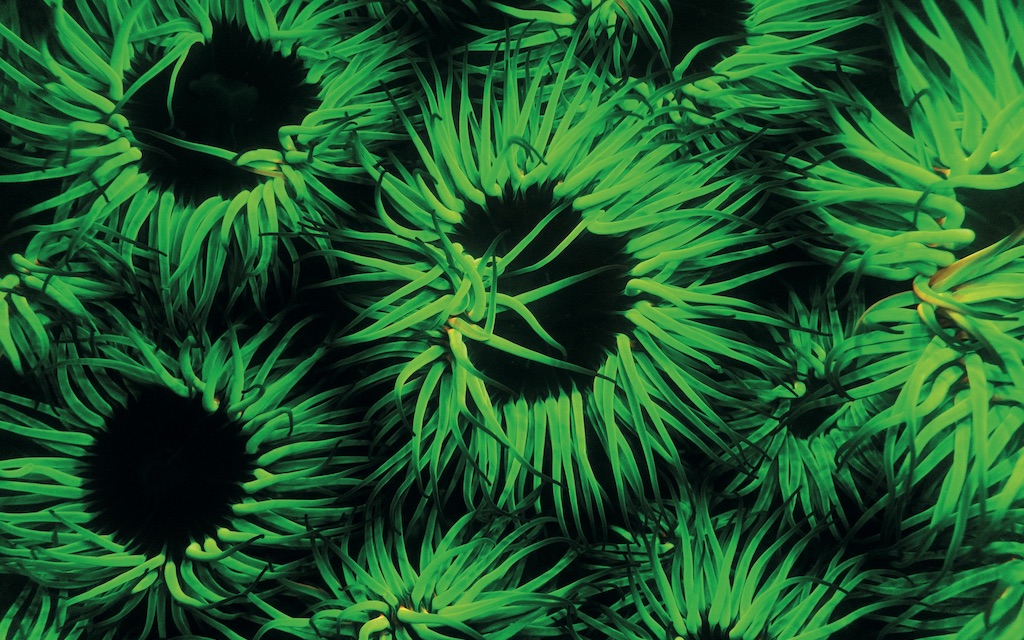

How very apt then that my first proper fluorescence dive was in Torbay too. At Babbacombe, to be more precise. Phillips’ report talked of a yellowish-brown anemone, so I had a hunch that I wouldn’t be disappointed because Babbacombe is home to many hundreds of snakelocks anemones, a creature already known to fluoresce.

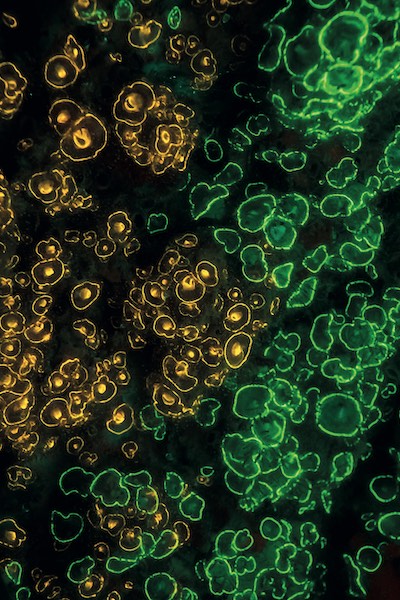

Being the salty old sea-dog that I am, and having celebrated 30 years of diving last year, it takes quite something to get me truly excited in my dotage. But this dive had my jaw dropping and eyes popping with boyish excitement. Quite simply – wow! My buddy and I enjoyed over an hour of swimming in our own version of Avatar, right here on planet earth. Every single snakelocks was glowing with greens, oranges and purples wherever we looked. And somehow the blue light seemed to cut through the mediocre viz better than our ordinary torches. To top it off we also found a patch of multi-coloured jewel anemones that were equally reacting to the blue light with a stunning light-show of their own.

It’s a good job the car-park was empty in the early hours of the morning when we surfaced because it wasn’t only my torch that was turning the air blue with excitement. Honestly, I’ve not had an experience like it in my 30+ years underwater. It was quite spooky to begin with, and I’m lucky to know that site very well, but once we got used to how different everything looked we enjoyed the experience immensely.

Fireworks party

Buoyed on by this first success, I began researching other likely targets that were known or suspected of showing this behaviour. Happily, as it turns out there are a few more species that do. One that is common throughout the UK is the light bulb sea squirt, Clavelina lepadiformis, which has a strong fluorescent reaction and can glow with subtly different colours too. On one dive I even came across a candy-striped flatworm whose stomach was glowing because it had recently eaten one of these sea squirts for dinner!

The two remaining species I had promising information on could both be found on my annual trip to the Scottish Highlands. I had discovered that in the Mediterranean Sea, a species of Cerianthus anemone fluoresces, and while that particular animal was not found in the UK, we do have the burrowing anemone Cerianthus lloydii, which looked like it could provide some promising results. The other anemone on my list is one of the most stunning you can see on any UK dive; the fireworks anemone. These majestic anemones are grace defined and can be found at relatively shallow depths in some of the Scottish sea lochs.

So armed with my, and by now favourite, new toy I headed the 600 miles north to explore in the dark once more. Usually heading off for a dive trip with heavy rain in the forecast wouldn’t normally make me smile, but in the sea lochs, the freshwater run-off creates a shallow layer of dark water (called a halocline) that cuts out a lot of the available light. The point being? Well, I could now effectively do nights dives in the middle of the day – meaning I didn’t lose any of my much-needed beauty sleep in the process.

Target one, the burrowing anemone, actually comes in two colours: a brown one (also very common in Devon) and an all-white variety too. On my second dive, I stumbled across one of each variety side-by-side. The white one looks stunning under the blue light where the brown one I found did not fluoresce at all. The sense of an alien inner glow is inescapable when I look at these photos, and I find it fascinating that – as far as I’m aware – science still is not utterly certain why some species display this behaviour.

In fact, there are a number of theories bounding around the scientific community as to why some animals (and plants too) do indeed fluoresce. For some, it is thought the fluorescence is a product of proteins held within the anemone that help to feed symbiotic algae inside the anemone that in turn helps to feed the host animal. In other species, it could be to prevent damage from UV light from the sun, and in others still, it could be some form of defence against predators. There is still much work to be done in all these areas.

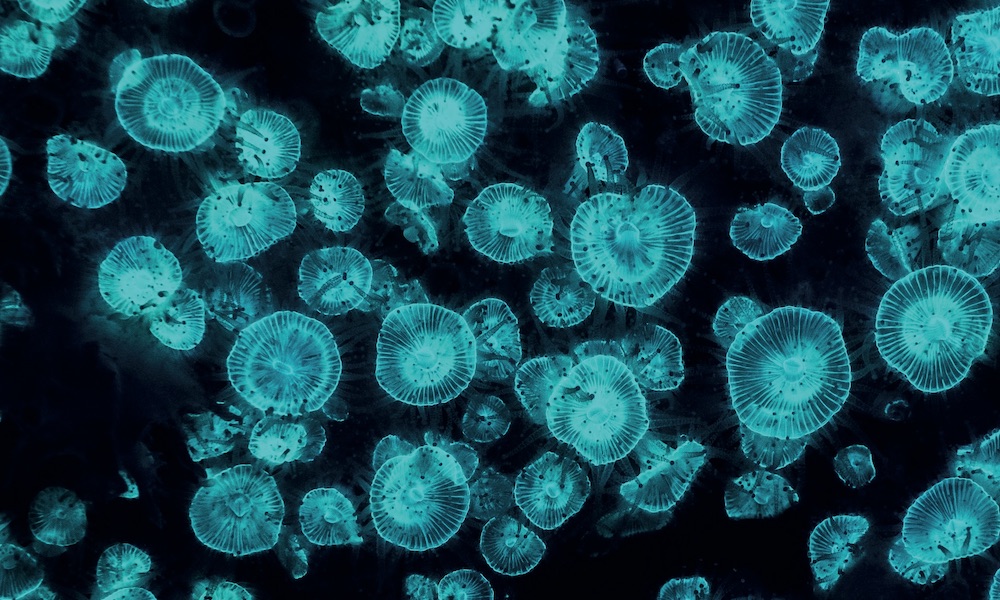

Back to target two, and the one I held out the most hope for, and luckily I found one not far away from where I found the two burrowing anemones. The fireworks anemone can have tentacles up to 30cm long, meaning that a large individual can reach nearly a metre across. But for all their size they are extremely delicate and do not like to be disturbed. If threatened they will curl their tentacles into tight coils in an attempt to protect them from would-be predators... or careless divers.

So approaching slowly over the silty seabed, and with extreme care, we managed to sneak up on a few individuals and turn on the blue light. We were in for a treat. Our first specimen was quite a dark one and showed only weak fluorescence, but our second was a pure white one which really did light-up as if someone had plugged it into the mains. It seemed somehow as if it was emitting a stronger light than the one we were shining on it.

As if to save the best to last, our final firework anemone we came across was a striped one. This individual still had the white tentacles but this time there were bands of a reddish-brown colour from tip to base. So on went the blue light and… pow! The firework display came to a jaw-dropping finale. Now we could truly see how fitting their common name truly is – for within each brown stipe there was a point of very strong fluorescence that clearly outshone the rest of the tentacle. It really did look like a large rocket had exploded in front of us; I’m sure I heard my buddy let out an ‘ooh’ and ‘ahh’ in appreciation.

I can honestly say this has opened up a new type of diving for me. ‘Fluorescence diving’ is nothing new on tropical reefs, but who would have thought you can get the same (I’d say better) experience right here at home. I also remain convinced there are more species that will show this same behaviour (I know some fish and crabs do) so I now have a whole new set of discoveries to work on... I can’t wait.

Lighting the way

The torch I use is a WeeFine Ring Light 3000, which is designed for photography. But because of its even light-spread, it turned out to be perfect for fluorescence diving. This model uses a broad-spectrum blue light (it also has white and red LEDs too) to bring out the fluorescence behaviour, but other torches use ultraviolet light to do the same. Depending on the type, and power, of light given off by your choice of torch you may need to use a ‘barrier filter’ on your mask. This is a bit of specially coloured plastic that only lets through the fluorescing light, making it easier to see.

Join the BSAC community

The BSAC network is working together to keep people connected to the sport. With online training, special interest webinars, competitions, support to clubs and the trade, and much more...we'd love you to join us.

This article was originally published in SCUBA magazine, Issue 85 December 2018. For more membership benefits, visit bsac.com/benefits.

Image credit: Dan Bolt

Author: SCUBA | Posted 06 Dec 2020

Author: SCUBA | Posted 06 Dec 2020