We think of the planet’s physical laws as immutable, but the magnetic North Pole on which our GPS tech depends is a moveable feast.

The Earth’s magnetic field is generated by currents in the liquid iron outer core about 2500km beneath our feet. The magnetosphere extends out into space and shields the Earth from solar and cosmic particle radiation and prevents the solar wind, a constant flow of charged particles, from stripping our atmosphere. At either end of the planet are the magnetic North and South Poles. However, neither magnetic Pole is located at the geographic Pole.

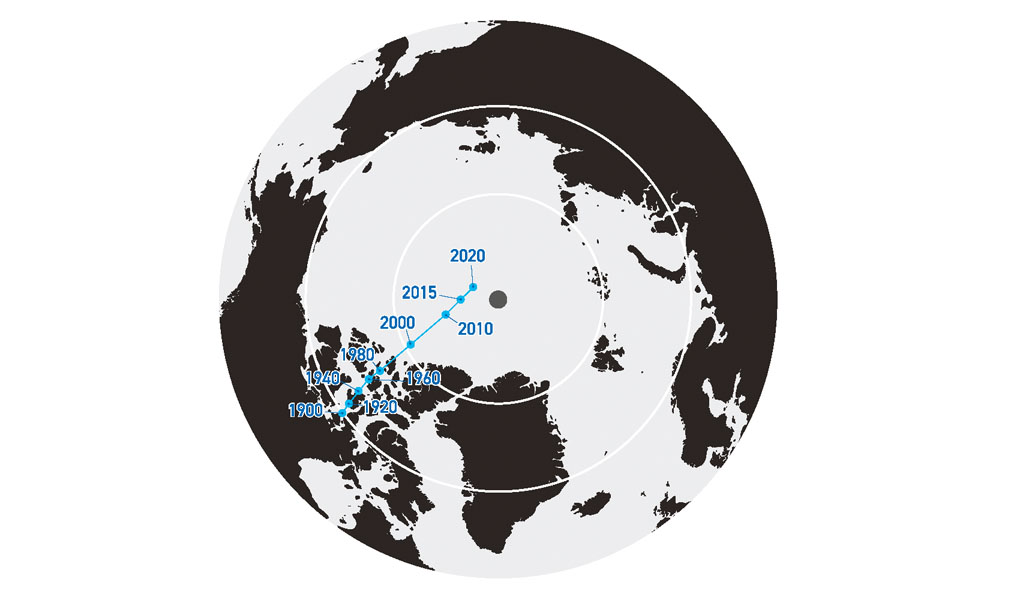

The magnetic North Pole was first located in 1831 in the Boothia Peninsula in the Canadian Arctic. The magnetic North Pole is never truly stationary because of changes in the flow direction and rate of the Earth’s molten iron core. Using historical data back as far as 1590, it’s possible to show that magnetic North has always wandered around the Arctic up to 2000km away from its location in 1831. Since 1831, it has been regularly tracked and it’s still moving. For much of this time, the movement has been quite slow, at around 9km a year, but from 2000 the speed had increased to 50km a year. The Magnetic North Pole is currently drifting towards Russia and appears to be slowing down a little (about 40km per year).

Anyone who’s looked at a marine chart will be familiar with the compass rose. This gloriously arcane image displays the local information for magnetic deviation (declination). The outer ring shows true bearings and the inner ring shows the degrees and minutes East or West of true North. In the centre of the rose is a reading of the magnetic deviation with a year, e.g. 4°15’W (2015) and an indication of how that deviation will change year on year, for example, 8’E. In this case, the deviation would be decreasing by 8’ each year. Count up the time between then and now, apply the right level of correction and away you go. Over time, the information in the compass rose needs updating. Lately, that information has become out-dated way before expected.

The UK and USA collaborate on producing the World Magnetic Model (WMM) which is used by all NATO countries and the International Hydrographic Organisation for magnetic compass navigation. Normally the WMM is updated every five years, but in 2019 an update was issued two years ahead of schedule. Smartphones and other electronics rely on the WMM for compass apps, maps and GPS services. As the Magnetic North Pole has moved at an increasing rate, it has become harder to keep up with the changes.

Both traditional marine compasses and fluxgate compasses rely on the interaction of magnetic material with the Earth’s magnetic field. Although the perception of fluxgate compasses is that they are more accurate than traditional compasses (as they aren’t affected by their position in the vessel or by rough weather) both types are subject to changes in declination.

Vessel chart plotters connected into the fluxgate compass (essential to run autopilots) get regular software updates to input the latest magnetic declination data. Paper charts either need to be reprinted, or you need to ensure you have the latest update. In recent years, the increased rate of change means these updates are increasingly important and while the Magnetic North Pole carries on its wandering, we all need to be aware of the impact this could have. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has a website with up-to-date declination information.

Throughout the Earth’s history, there have been periods of excursion when the magnetic North Pole goes for a wander, sometimes by up to 45° with a reduction in the intensity of the field. The magnetic South Pole is currently 25° from the geographic south pole. The frequency and duration of excursions appear to be random. The most recent event was about 41,000 years ago and lasted 440 years. The magnetic field was nearly completely reversed for 250 years.

A full reversal of the poles has happened 183 times in the last 83 million years, with periods of stability lasting up to 10 million years (although some are much shorter). The current stable period has lasted 780 thousand years. Are we witnessing the build-up to a full reversal? It’s hard to tell and in any event reversals take hundreds to thousands of years to complete, so we will never know!

BSAC members save £££s every year using BSAC benefits.

Join BSAC today and start saving on everything from scuba gear, diving holidays and diver insurance, to everyday purchases on food, online shopping and retail with BSAC Plus. Click to join BSAC today.

This column was originally published in SCUBA magazine, Issue 101 April 2020.

Images in this online version may have been substituted from the original images in SCUBA magazine due to usage rights.

Author: Michelle Haywood | Posted 25 May 2020

Author: Michelle Haywood | Posted 25 May 2020