You’ve been at sea for a while and felt fine, but back on dry land everything seems to be rocking under your feet. Michelle Haywood explains this unusual sensation.

Many divers suffer from seasickness; I’ve written before about how the various pharmaceuticals work to help settle that awful feeling [Battling seasickness on boat dives, September 2020]. However, for some divers the opposite is true, they suffer from land sickness. The official term for this is Mal de Terre (from the French). For sufferers, it means that they are unlikely to get sick while on the boat, but when they step onto dry land, the floor feels like it is still moving beneath their feet.

Many people will feel this for a short period of time, but in rare cases it never ends. This is the more extreme Mal de Debarquement Syndrome (MdDS). Sufferers will still be rocking and feeling nauseous for months or years. It’s not just sailors that can suffer from MdDS. It can be triggered by roller coasters, flight simulators or even sleeping on a waterbed. Women aged 30-60 are more susceptible. MdDS is thought to be due to problems in the brain processing sensory information and not readapting once motion has stopped.

What causes Mal de Terre?

The factors that contribute to susceptibility to Mal de Terre can be a little bit of a mystery. It can help to avoid heavy meals and alcohol during a boat trip – but that’s not usually an issue for divers (unless you’re on one of those liveaboards that insist on feeding you within an inch of your life). Doctors may prescribe anti-sickness medications to help you get through it. Mostly, symptoms disappear after a couple of days and your land legs return.

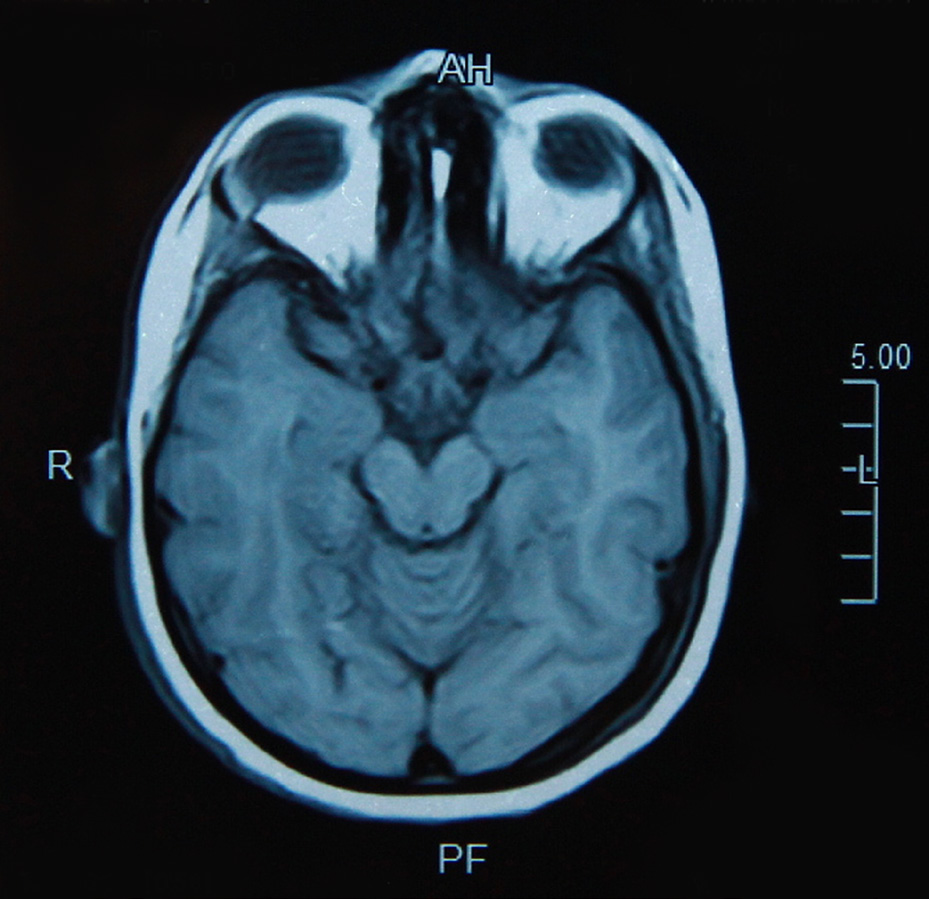

Mal de Terre is likely caused by events in the inner ear. Loop-shaped canals in your inner ear contain fluid and fine, hairlike sensors that help keep your balance. At the base of the canals are the utricle and saccule, each containing a patch of sensory hair cells. Within these cells are tiny crystals of calcium carbonate, called otoconia. Otoconia help monitor the position of your head in relation to gravity and linear motion, and are usually held in gel in the utricle. When these crystals get dislodged, they can enter the semicircular canals and generate a false sense of movement.

Fluid in the semi-circular canals does not normally react to gravity. However, the crystals do move with gravity and, when they move, they cause the fluid to move more than it normally would. When the fluid moves, the nerve endings in the canal are excited and send information to the brain that the head is moving, even though it isn’t. You can imagine little crystals creating little waves of fluid from the slightest movement. Little wonder that sufferers’ brains get confused, and nausea ensues.

‘In contrast sea sickness, Mal de Terre is caused by the brain’s failure to re-adapt to no motion'

Recovering from Mal de Terre

But there is hope. In 1980 John M Epley described a repositioning manoeuvre that helps settle the crystals back into their proper place. The patient begins sitting upright with legs fully extended and the head at a 45-degree angle. The patient gets lowered quickly backwards, keeping their head to one side and extending their neck. After a couple of minutes, the patient turns their head 90 degrees to look the other way. After another couple of minutes, keeping the head and neck still, the patient rolls onto their shoulder so they are now facing downward towards the bed. A couple of minutes later the patient sits up (with their head still at an angle) and stays still for 30 seconds. The whole routine may need to be repeated a couple of times.

The goal of the Epley manoeuvre is to allow the dislodged otoconia to settle back into the utricle. Once the otoconia is no longer sloshing around in the semi-circular canals, the land sickness resolves. Fluid in the canals is no longer being pushed around by the errant crystals. It takes some practice to work out where your head should be, and which way you need to roll; it would probably help to have someone reading out the instructions to you for the first time you try it. However, it’s a drug-free way to settle cases of Mal de Terre and it’s definitely a manoeuvre worth knowing about.

I'm ready to learn to dive, help me find my local BSAC club

Send your postcode to hello@bsac.com and we'll send you your three nearest scuba clubs. Or if you fancy a chat call us 0151 350 6201 (Mon - Fri, 09:00 - 17:30).

This column was originally published in SCUBA magazine, Issue 119, October 2021. For more membership benefits, visit bsac.com/benefits.

Images in this online version may have been substituted from the original images in SCUBA magazine due to usage rights.

Author: Michelle Haywood | Posted 10 Nov 2021

Author: Michelle Haywood | Posted 10 Nov 2021