The problem with trio diving was brought home to Chris Oakley when he suffered an inexplicable kit failure while separated from his buddies.

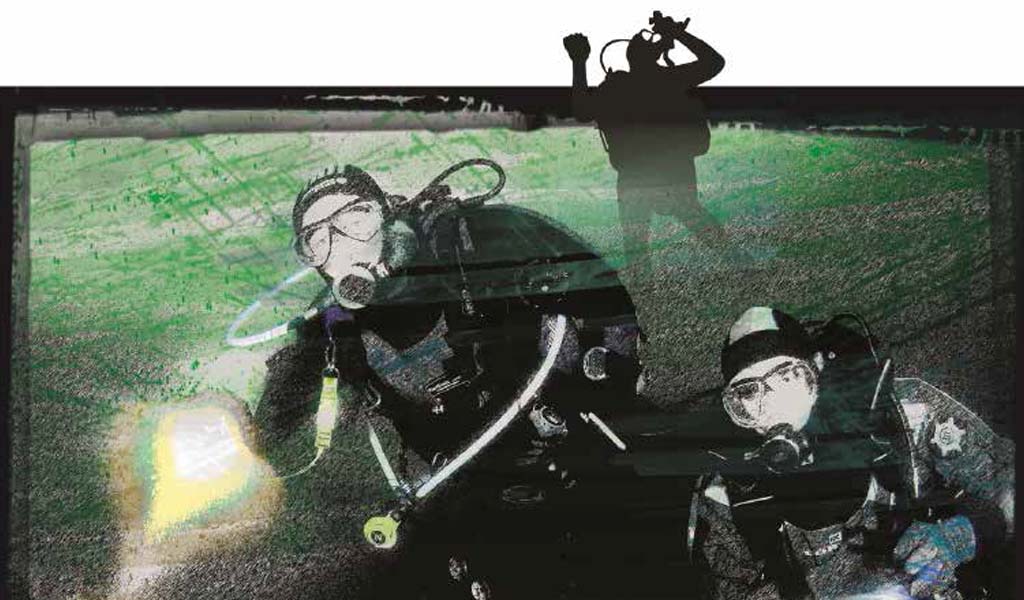

A few years ago I was at Stoney Cove for another regular visit. As a Dive Leader, I was looking forward to another day of diving with friends. After one successful dive and after our break we entered the water again but as a three-man dive: two Dive Leaders and an Ocean Diver. We were comfortable with this arrangement, but as we all know you should dive in pairs as one is in effect left diving alone, as I was to find out.

We entered the water and descended down to 18m. The visibility was poor, only a couple of metres as we swam over to the single deck bus to look around. We were only 11 minutes into the dive when I noticed it was getting difficult to draw air from my regulator.

I looked at my computer, which told me I had 189 bar in my 15L cylinder, but as I checked this it became apparent that my kit was failing me. I switched over to my pony system and had a quick look around for the other two divers, but due to the poor viz I couldn’t see them: I was on my own. Instead of making my way to the surface, I tried to rectify the problem and look for the others at the same time; however, by doing this I was wasting valuable time and air.

Mindful of the problem, I knew I only had seconds left in my bailout gas supply, which was about to run out. I realised, too late, that this was now a full-blown emergency situation. My pony air supply ran out and I knew I would not make it to the surface.

With no regulator in my mouth, I accepted the fact that I was about to drown, desperately holding my breath and knowing I only had seconds before I would eventually have to breathe in and end it all. It was a very strange feeling, as I became really calm and accepted the fact that I was about to die. I remember wondering who would tell my wife, and what would they say?

It was at this point that I had to do something and quick. I swam down and in the direction of the Stanegarth wreck, which I knew was our planned route. Literally, within seconds I saw a flash of orange which I knew was the other Dive Leader’s BCD. I grabbed onto him, quickly located his octopus and took a long, life-saving breath of air, screaming at him through the regs that we needed to surface. All three of us started our ascent but my buddy could not get any air into my stab jacket, he tried desperately to inflate my jacket with some air to start our journey to the surface. But my kit just would not work. So, using his jacket and a lot of finning on my behalf we eventually hit the surface.

I had never been so relieved in all my life.

Once we got to shore I checked my kit and found it was now working and this was a complete mystery which no one could explain. The following day I contacted Apeks and explained what had happened as I was using Tungsten XTX 200 regs. The guys at Apeks were fantastic and asked me to bring them all my kit used on that dive, which I did. They inspected and tested everything, but could find nothing wrong with any of my kit. But they did explain that they knew of this happening once before and they explained that the last time it happened it was a fault in the valve on the cylinder. However, they could not confirm 100 percent this is what happened with my kit. But as a safety measure they changed the valve and I’ve had no problems since.

To summarise, this was a very close call which no one could have predicted. I have always looked after all my kit and had it serviced as required. As a former member of the military, I am a stickler to adhering to procedure and checking everything twice. I also feel that the training I received as a BSAC diver and the experience gained through my military service helped me to remain calm and in control throughout this emergency.

A response from APEKS

We take incidents like this very seriously and carry out thorough investigations if ever they occur. Our regulators are designed in such a way that a gas shut-off is not possible, any failure mode would result in a constant flow of gas, so the diver would always be supplied.

It is a very rare occurrence for the gas supply to stop if there is still gas in the cylinder, and the only time we have known this happen, is if there has been a fault or restriction with the cylinder valve. We always ask that the cylinder valve is investigated when possible, unfortunately with overseas hire equipment, it is not. Although we know the regulator cannot fail in this way, we will still ensure that everything is done to support the customer and give them back the confidence in their Apeks equipment

Incident analysis by Sarah Conner

Incident analysis by Sarah Conner

Talking with Andy Procter about this year’s incident report, he mentioned a few common factors year on year, one of those was diving in groups of three or more rather than as a buddy pair.

If you are diving in a three, you need to be extra vigilant about staying together as a group; in poor viz, touching distance or line of sight is a good rule to work to.

The normal one minute to look around then regroup with your buddy at the surface could be reduced to 30 seconds in poor viz, or otherwise challenging conditions. If there are any kit issues, especially with your life support equipment, the dive should be terminated and a safe ascent to the surface should be immediately made.

It’s worth calculating how long your gas supply (for main and your redundant sources) will last at the maximum planned depth. Try planning for both normal and stressed breathing rates. Ideally, this should be noted as part of every dive plan, so the facts will be in your head should you deviate from the plan.

Pony cylinders are typically only 3-litre and thus don’t last very long, especially when divers are stressed. You are not supposed to use them to continue a dive, but to abort and head safely to the surface. That was the critical mistake here.

It’s worth keeping your regulator in your mouth when your gauge shows empty; as you ascend, any residual gas could expand sufficiently to give you one more partial breath. Training also teaches us never to hold our breath; unless we have emptied our lungs any residual gas in them will also expand, possibly leading to barotrauma.

In dire circumstances such as running out of gas, ditching weights and having an emergency ascent to the surface – the only place you can be certain you can breathe – is the safest course of action.

Rescue and self-rescue skills are sometimes only practiced when people are preparing to move up a grade, but it’s worth keeping your skills fresh in the pool or shallow open water. Join a session with instructors present who can review your skills and keep you up to date with BSAC best practice. These review skill sessions can even be made into a fun day of role-playing.

Help us to keep diving safe

You should report any diving incident in confidence to the BSAC Incident Report (All incidents used in the report are anonymous).

Sarah Conner is an Advanced Instructor and former BSAC regional coach. In addition to being an accredited HSE commercial and cave diver, she is qualified to use hypoxic trimix on open and closed circuit.

Got a similar story?

Do you have an instructive drama in which you took control of a difficult diving situation? If so, we’d love to publish your story in SCUBA magazine and online. SCUBA now pay £75 for every story published. For more details and a briefing, email the Editor Simon Rogerson.

Author: SCUBA | Posted 09 Jan 2018

Author: SCUBA | Posted 09 Jan 2018