Dr Daisy Stevens sets out the need-to-know on a condition of which every diver needs to be aware.

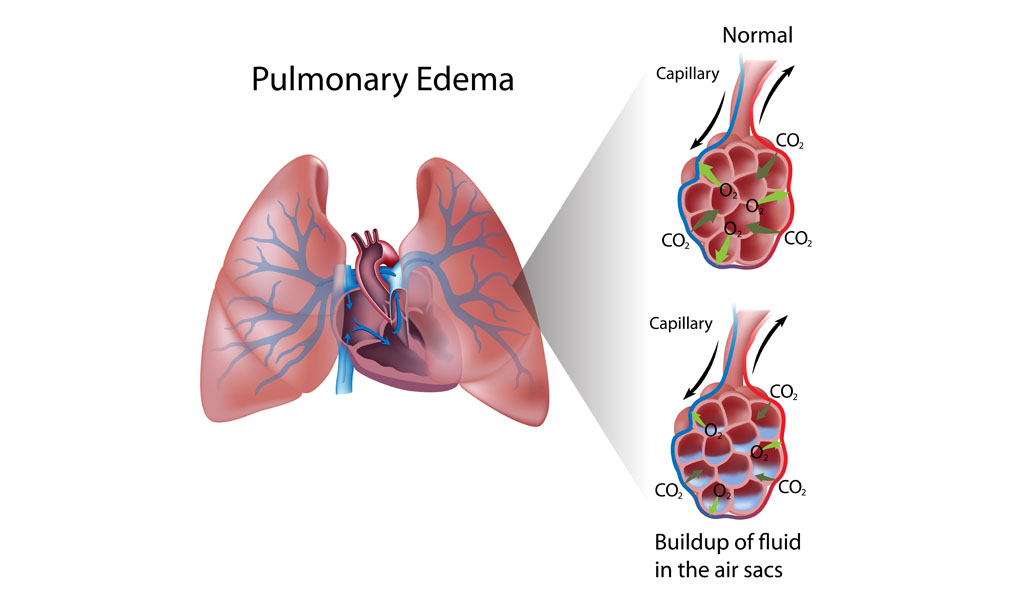

Immersion Pulmonary Oedema (IPO) is the accumulation of fluid in the lungs whilst immersed in water. In the United States, it is referred to as Immersion Pulmonary Edema (IPE).

Why does IPO happen?

As we enter the water, the hydrostatic pressure collapses veins in our limbs, which hold between 500-800mls of blood, increasing the volume of blood returned to the heart.

When a diver is cold, peripheral vessels constrict to preserve heat, pushing more blood into the central circulation. The increased volume can overwhelm the ability of the heart to pump blood from the lungs to the body, and therefore the backpressure exerted allows fluid to leak into the alveolar spaces.

Other risk factors

- Cardiovascular disease (high blood pressure, irregular heart rhythms, previous heart attacks and heart valve abnormalities) affects the heart’s ability to cope with the increased blood return.

- Excessive blood vessel constriction can occur without a diagnosis of high blood pressure. Often because of cold water or stress, the body mounts an exaggerated blood pressure response. This can even occur in physically fit athletes or military personnel.

- Overhydration before diving leads to an increased total blood volume.

- Tight wetsuits / drysuits enhance the hydrostatic pressure of water, compressing veins, and returning blood back into the central circulation.

- High negative inspiratory pressures from breathing apparatus. If the inspiratory counter lung from a closed circuit rebreather (CCR) is positioned higher than the lung centroid, there is a negative pressure difference. This creates a local hydrostatic pressure difference when the diver takes a breath in, drawing fluid into the alveoli. The same mechanism is responsible for poorly maintained regulators when a greater effort is required to take a breath. Snorkellers also have a negative inspiratory pressure related to the air above them.

- Exercise or exertion in water. It’s not only divers that get IPO! Regardless of whether you are swimming on the surface, snorkelling, or diving, IPO can occur. As respiratory rate and effort of breathing increases, a negative inspiratory pressure is formed, drawing fluid into the alveoli.

What symptoms should I look out for?

The symptoms of IPO include:

- shortness of breath

- difficulty breathing (often feeling as if you have run out of gas, or regulator failure)

- a cough with or without frothy / blood-stained sputum and dizziness

If this happens at depth, divers need to ascend to the surface, which will drop their inspired partial pressure of oxygen (pp02). This higher pp02 may have been protective by keeping oxygen levels in the blood high enough to perfuse the brain; as the levels drop, hypoxia results and the diver may lose consciousness.

What do I do if I think someone has IPO?

The most important action is to get the diver out of the water. Be mindful that the ascent will lower their pp02 and may increase symptoms in the short term. Make sure you stay with them until they make it to safety!

Once out of the water, the hydrostatic pressure is eliminated and blood distribution returns to the peripheries. Remove tight-fitting gear and place them on high flow oxygen. If oxygen is not available, rich nitrox can be used. Call 999 and while waiting for the ambulance try to warm the diver up; being sat up may help their breathing if they can tolerate it.

Often, exiting the water is enough to make a significant improvement, however, despite this, it is important that divers are assessed at the nearest emergency department. Unfortunately, IPO is a life-threatening condition that often happens again. It would be unsafe for a diver to return to diving after an episode of IPO unless a definitive cause can be identified and reversed.

To learn more I recommend watching Dr Peter Wilmshurst, the worldwide expert on IPO, speak at the BSAC Diving Conference 2017.

Interested in diving health and medicine?

This column is produced with DDRC Healthcare, specialists in diving and hyperbaric medicine. You can find out more on their website.

This Anatomy of a diver column was originally published in SCUBA magazine, Issue 102 May 2020. For more membership benefits, visit bsac.com/benefits.

Images in this online version may have been substituted from the original images in SCUBA magazine due to usage rights.

Author: DDRC Healthcare | Posted 13 Jun 2020

Author: DDRC Healthcare | Posted 13 Jun 2020